This is not to say that by "radical liberation," I mean that women should have been or should be ordained to the priesthood, but rather, that women enjoyed much greater freedom and notoriety in the first two centuries of Christianity than they likely had in the first two centuries before it, directly tied to Christ's inclusion of them in his ministry and their subsequent prominence as consecrated virgins, widows, deaconesses, and martyrs in the Early Church.

Yet, there was a backlash. Especially in the Middle Ages, Western society continued to devalue the roles of women, and even my beloved St. Thomas Aquinas wrote against the idea that a woman should lead or teach in any faculty outside of her household. The 20th Century inherited this bias, as did, I surmise, the feminist movement, so that even the traditional roles of women such as bearing and educating children and keeping house were viewed with disdain as menial tasks and symbols of oppression.

This is a great tragedy, for God reveals our Scripture that woman is not a replacement for, but a helper to man, equally the imago Dei. What role can she play, though? To say that she bears children is well and good, but what of her purpose after this, or if this never occurs? Is there a ministerial role she can have? For many, myself included, there is a strong desire to be faithful to the teachings of the Magisterium, but the gender (sex?) restriction for the sacrament of holy orders remains a perceived injustice.

Now, Augustine and Thomas speak of a lack of a certain spiritual capacity in the soul of a woman that -- despite being made in the image of God and having equal capacity, therefore, for salvation --prevents them from taking certain roles. Mulieris Dignitatem and Ordinatio Sacerdotalis speak of the equal dignity of the sexes, however, without really defining "dignity." I assume we might use Thomas's definition that dignity is that which "signifies something's goodness on account of itself." I wonder what sort of lack of spiritual capacity would enable a woman to yet have equal dignity? My thought is perhaps that if females lack one spiritual capacity that a male has, perhaps a male then lacks one that a female has.

John Paul II spoke of the idea of "motherhood" as extending to the spiritual domain, and in general, I find that helpful, but not in all instances, because I'm not certain that "motherhood" or "fatherhood" get at the heart of the "(lack of) Women's Ordination" problem in sufficient ways. A priest isn't merely a "father," but he acts sacramentally in persona Christi.

I think perhaps part of the clamoring for women's ordinations comes from a continued devaluing of motherhood: a failure to appreciate what an amazing calling that truly is. Again, though, I'm not certain that a revaluing of motherhood is the entire solution - though it should be pursued with great fervor. For my part, I've been musing about what Mary showed us womanhood could be in an analogous sense:

Mary, as woman, was the New Eve, the Ark of the New Covenant, and the Theotokos,

As the New Eve, she is obedient to God where Eve had failed.

As the Ark of the New Covenant and the Theotokos, she is the Bearer of the Word.

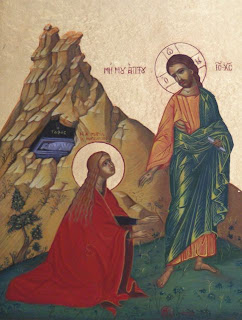

Yet she is not the only woman in the New Testament to be so... The women at the tomb are also bearers of the Word, the first witnesses of the Resurrection. Constantly, where the men of the gospel narrative are bewildered, women seem to have unique insight into just who and what Jesus is.

What is the male response? Proclamation. The Ark bears the Covenant, the Covenant is God's Word, the Word is Proclaimed. The Evangelion first comes to the men through the women, and the men proclaim it. Mary approaches Elizabeth, bearing Christ in her womb, and John himself, not much further along, leaps within the womb. I don't think this is an exhaustive notion - it's merely an analogical model, but...

Is this role of Mary indicative of a spiritual capacity, found in women par excellence, that we are not recognizing? Could this capacity be sacramental (it did indeed mediate grace, and Christ, in a manner of speaking, did institute their unique place in bringing him forth) ?

And what of the question of sex vs. gender? To what degree must someone identify as male to be considered male, or is it merely a question of biology? Can we still use a (JP2's?) notion of male-female complementarity? How can we shape our ministry to encompass those who would seek Christ yet have, in the words of Thomas, "some obstacle" which confounds our either/or model which doesn't take into account what current gender theory seems to suggest: that gender, sex, and sexual orientation, while related, are not the same things?

Whatever answers can be given for these questions, there are a few things that we must assert: Women are of equal dignity, and their unique proclivities as women must be elevated and valued to represent this. We must acknowledge in all areas of culture that they are people of dignity, not to be denigrated for their beauty to the male eye (and made to be objects of lust or adornments), not to be thought weaker for their role in motherhood (but rather, stronger), and not to be thought unable to accomplish something because of any accident of their soul (we must avoid falling into the archaic "fairer" / "lesser" sex mindset). We must also endeavor to respect, trust, and be obedient to the Magisterium in this regard as well, despite having the courage to challenge weak arguments and leaps of logic, so that what is true and what is just is what is affirmed not merely in content of Church teaching but in form and expression in letter and practice.

No comments:

Post a Comment